5 Steps to Creating Impactful Tech Projects

At Vegan Hacktivists, one of our top priorities as we’ve grown as an organization is to consider the impact of our projects by ensuring that they are as usable and useful for users as possible. It is a tall order. How do you not only design and build something that is useful and usable, but also one that could be supported and coordinated by a team of remote volunteers?

This is something that any organization can struggle with. I’ve even found it’s difficult to get full-time, salaried employees to collectively focus on ensuring their projects have impact. Good ideas are fantastic, but ensuring that a project is used in the real world is a different matter altogether.

In order to help achieve impact through making projects, I’ve found you have to rethink how you go about creating projects—you start asking deep questions about why and start considering experiences rather than just outputs.

With input from other volunteers, I began to put together a project process that would help ask these questions. As part of this, there were a number of integral challenges to address.

The Key Challenges

In my day job, I lead user experience design at a tech-for-good company in the UK. My job involves me leading a team who researches the behaviors and needs of different groups of users and designs products for them.

In my day job leading user experience design, I have found that creating a digital product isn’t always very collaborative in practice, despite claims to the contrary. Often, different fields—designers, marketers, or developers, for example—aren’t included at the right times or aren’t afforded input at important decision points. Moreover, I’ve found it’s often the case that these different fields don’t always feel like they were part of the process, and instead more like cogs in a machine.

When I joined Vegan Hacktivists, I found that there was sometimes a gap in ensuring that the right people were involved at the right time. We needed to know who was needed when, and when they could contribute. This was especially true for user experience designers and researchers, who need to be involved at times you might not expect.

But there was one other set of challenges I noticed.

Traditionally, designing and building software has been focussed around solving particular issues. The main goal is getting a project delivered, which focuses on outputs, and finding out what needs to be done, how and by whom.

The challenge with these more “traditional” mindsets is that they don’t necessarily ask important questions about purpose and vision. Namely: why is this project important? What are our goals in building it? How will it be different? How will the users use it? I found that there was an opening to ask these kinds of questions more robustly and systemically at Vegan Hacktivists.

By asking these kinds of questions, by democratizing these sorts of questions among those who are building the project—organizations can ensure that everyone can understand, feed into, and interrogate the purpose, value, usability, and vision of the project.

This is obviously very important for ensuring that the project can be effective and impactful, but also helps to drive up motivation and empowerment among team members. These methods can even include end-users (e.g. through participatory design), which further strengthens and democratizes ownership of a project.

Given these goals of ensuring incorporation of the right people at the right time, ensuring that everyone has sight and input of a project, and ensuring that projects are impactful and effective through high usability and utility, I set to work on building a project process for Vegan Hacktivists.

Let’s break down that process, covering the key steps.

Step 1: Defining the Idea

The first step in building any sort of digital product is to define the idea. This is vital because it codifies what we think the product will do, how it will do it, and why it’s better than other products. It can take many forms, but here’s the rough structure I put together:

There are [a group or type of people] who [need a problem solved] so that they can [have a particular good outcome].

Currently, they [what alternatives they use and why they aren't good].

If we [provide a solution that does something], then [the experience and outcomes will be better because of these reasons].

I’ve called this a “project idea hypothesis” and the person who ‘owns’ a new project idea can fill it in as best they can. By using this to identify who the audience is, what the challenges we are trying to solve for them are, and how we can improve their outcomes, we can ensure that we are being transparent and clear on why we are doing what we are doing. In other words, we each don’t have different ideas of what we are trying to do.

Getting everyone on the same page by “externalizing” (that is, getting things out of people’s head onto paper or some sort of digital document) helps form consensus around a mutual picture of where we are going, and the route we’ll take to get there. This also enables us to test this hypothesis. Is it accurate? Well, this gives us a focus for research to find out.

In order to help shape this research, we can ask a number of other questions:

How do you know the problems you’re solving really exist?

What are the current alternatives to the problem?

How is the proposed solution better than current alternatives?

How will it be made obvious that our solution is better?

How much effort will it be to design and build this solution?

Drawn from the Venture Design process and Lean UX, these questions can help us identify if this idea is suitable and plausible. Once we’ve completed research to answer these questions, we can decide if it is worth following through and if so, we can get into the veggies (not meat…) of the project.

Step 2: Defining the Experience

It’s too easy to just jump in and start designing and building an interface. The problem with doing this is that we all might have different ideas about how the project could unfold. What’s the scope? What will be the steps the user takes to interact with the product?

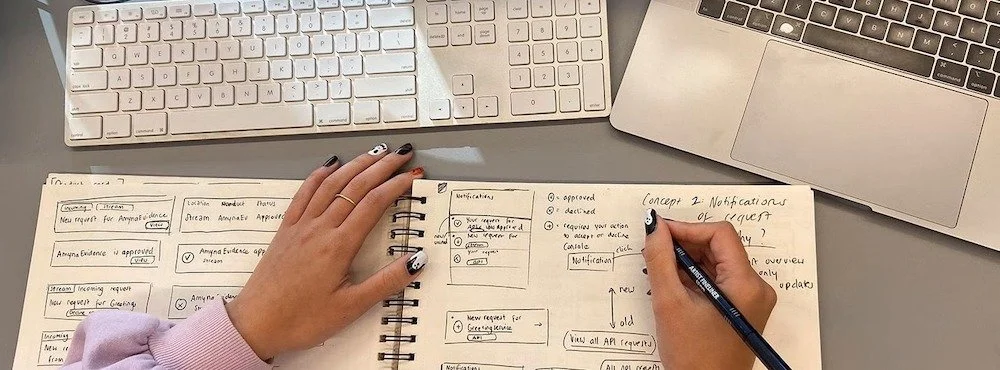

By building out user flows, which chart a user’s experience through a web interface, we can understand all of the steps a user might need to undertake from beginning to end and flag any problematic or uncertain areas. This is also an opportune time for developers to begin specifying the technical functions. This can help identify what is possible and what isn’t.

At this time, the marketing and communication team can begin thinking, “Is this marketable? How would we market it?” And the data team can begin asking, “How would we measure the success of it?"

Each of these areas can build into how the project is designed, what types of things should be emphasized, what things should be avoided, and what the constraints may be. Importantly, new opportunities can be identified as well.

Finally, once we have any basic idea of the project (through wireframes or simple mock ups), we can test it with people to gauge their response. Is this something people are interested in? Something they’d use? Depending on the situation, we can shelf the project, pivot it to something that works better, or continue as normal.

Step 3 & 4: Design and Development

Assuming the project passes all of those hurdles, we can move on to design and development.

This step should begin when we have certainty of the experience, including wireframes or flows that detail the scope, steps, and user’s experience at a high level.

We can start creating the branding, the interface, and both UX copy and marketing copy. All of this defines the actual nuts and bolts of the product, the detail of the messages it is trying to get across, and quite literally what developers should build.

Once we are happy with the designed product, we can begin building. This involves developers working on the front-end (all the stuff a user sees) and the back-end (the stuff the user doesn’t see, such as the database).

Step 5: Marketing and Evaluation

Once the project is built and live, we can begin implementing our marketing and communications efforts to get the word out about it.

But the work isn’t done there. We need to evaluate how the project is doing, relative to our expectations (remember the project idea hypothesis?). We can do this by bringing in teams who can research it qualitatively, such as through user testing, and understand any potential problems with the usability or comprehensibility of the site. The data team can also look at how people are using it in terms of raw numbers, such as the point in which people stop using the product

And that’s it! In reality, projects like these are never quite done. To continue building features and making changes based on user feedback, a coordinated effort between all teams within an organization is a necessity. We are always improving on what we do by applying what we learn through our ongoing evaluations of the product. This is how we build projects that are not only impactful, but also can meet the changing needs of its end users.